By John Ross

The attempt at the Trump-Putin summit in Alaska on 15 August to reach an unconditional ceasefire in the Ukraine war was inevitably bound to fail, as it would simply mean in practice a beneficial pause during which Ukraine, which is in a worsening position in the war, would be rearmed by NATO — and, as this is transparently clear, it was bound to be rejected by Russia. Such a one-sided proposal will therefore also continue to fail despite attempts by European leaders and Ukraine to revive it at, and following, their own summit with Trump on 18 August. The proposal by the European leaders is in reality, therefore, one to continue the war, and for its outcome simply to be decided on the battlefield. As Ukraine is currently losing the war, and has no realistic prospect of reversing this without a direct intervention of NATO military forces, which would threaten a World War, and which for that reason NATO is not prepared to undertake, all that Europe’s leaders are proposing is the loss of many tens of thousands, probably hundreds of thousands, of Ukrainian and Russian lives at the end of which the Ukraine will still lose.

This is a helpful outcome only for those cynical and destructive political forces, which do exist in the U.S. and Europe, who see the continuation of the war as an end in itself — in the hope that it will weaken Russia. The outcome of these summits, therefore, makes clear that there will not be a rapid outcome to the war and once again focuses attention on the fundamental issues which created it – with its disastrous consequences.

Ending the Ukraine war is, in turn, a vital step for Europe to get out of the economic, social and political crisis which has been worsening for years — and which has imposed great damage on the rest of the world.

The common framework of both the U.S. and European leaders towards the summit was a reactionary one of a division of labour in which Europe will undertake a large scale military build up in order to strategically create conditions for the U.S. to devote less of its military resources to Europe and more to its attempt to confront China. As an additional goal the U.S., in particular, has been seeking control of Ukraine’s mineral resources.

Within that framework there are simply tactical differences. Trump, who sees the U.S.’s main strategic goal as to separate the close relations of China and Russia — which is a combination creating very serious difficulties for the U.S. — has been prepared to envisage some concessions to Russia in an attempt to achieve this — although not ones which will meet the chief issues which lie at the root of the war, the eastward expansion of NATO and the rights of the large Russian speaking minority in the Ukraine.

The reason European leaders also put forward proposals which clearly cannot end the war— most recently in the joint statement by Macron, Meloni, Merz, Starmer, Stubb and von der Leyen on 9 August, ahead of the Trump Putin summit — is also because they refuse to adopt a policy which settles the two interrelated issues which led to this catastrophic war. Their proposal for an unconditional ceasefire was even more unviable given the admission by Merkel, not contradicted by any European leader, that the Minsk ceasefire agreements in 2014 and 2015 were used and seen by European leaders and NATO as an opportunity to qualitatively reinforce Ukraine’s armed forces.

The first fundamental reason for the war was the entirely predicted disaster of NATO’s expansion into Eastern Europe —in particular the attempt to incorporate Ukraine into NATO. Numerous US experts on Eastern Europe predicted this ruinous result in advance — led by George Kennan, the original architect of US Cold War strategy, who warned NATO expansion would be “the most fateful error of American policy in the entire post-Cold War era”. This warning has been entirely vindicated.

The reason is obvious. The attempt to expand a military alliance and its resources up to the borders of a major power, particularly the most sensitive parts of its border, will not be accepted and will inevitably lead to crisis.

Th U.S. itself should have easily understood this. At the time of the 1962 Cuban missile crisis the U.S. made clear that it would not accept the presence of Soviet missiles in Cuba and would go to any lengths, if necessary nuclear war, to stop this. The reason was obvious — the distance from Havana to Washington is only 1,100 miles/1,800 kilometres, the flight time for a missile over such a distance is so short that military defence is impossible. But, in comparison, the distance from Kyiv to Moscow is only 470 miles/750 kilometres, less than half the distance of Havana to Washington! Furthermore, Ukraine is a traditional route of conventional military attack on Russia – as seen both in the 1941 Nazi invasion “Operation Barbarossa” and in the 1942 campaign that culminated in Stalingrad. Russia therefore repeatedly explicitly stated that Ukraine’s membership of NATO was a red line for it. The U.S. was therefore demanding that Russia accept military conditions which the U.S. made clear it would use any means to stop if applied to itself.

Second, Ukraine, was a bilingual/binational state. The east and west of Ukraine were historically separated by language, religion, and history – in short, there was a national question within the Ukraine between a nearly 30% Russian speaking minority, as found by the 2001 census, and a Ukrainian speaking majority.

Bilingual/binational states, with very large minorities, can be kept together. Within Europe Belgium is an example and in North America Canada is. But the precondition for unity is acknowledgement of the national/linguistic rights of both groups and protection of a minority.

For example, in Canada unity was maintained only by a strict bilingual policy under which even in parts of the country where there are almost no French speakers, or English speakers, all signage must be bilingual, both French and English may be use in the legal system, in commercial transactions, in government etc. Even with these conditions Canadian unity has only been held together by a very narrow margin – in the 1995 referendum Quebec voted against independence by only 45,000 votes, a vote of only 50.6% against. If there had not been a bilingual policy, or policies unacceptable to the French speaking minority had been embarked on, Quebec would certainly have voted in favour of independence.

But after 2014 in Ukraine a systematic policy of institutional discrimination against the very large Russian speaking minority was embarked on. As the Council of Europe’s Venice Commission, which certainly cannot be accused of being pro-Russian, stated: “the current Law on National Minorities is far from providing adequate guarantees for the protection of minorities… many other provisions which restrict the use of minority languages have already been in force since 16 July 2019”. The inevitable result of such a policy was to destroy the basis of the unity of the bilingual/binational Ukrainian state.

These two issues inevitably interrelated, because the Russian speaking minority did not support membership of a pact, NATO, which is clearly aimed against Russia but had favoured neutrality.

Independently of any view of the present government of Russia the statement by Russia’s foreign minister Lavrov is accurate that if it had not been for the 2014 coup against the elected Ukrainian government, the discriminatory laws against the large Russian speaking minority, and the cynical use of the Minsk I and Minsk II ceasefire agreements to simply reinforce Ukraine’s military forces, the Ukrainian state would still exist today in its borders established in 1991.

But with the combination of overt discrimination against the large Russian speaking minority after the events of 2014, and the attempt of Ukraine to join NATO, which together were the strategic policies which led the 2022 war, it is in practice impossible to restore the unity of the former Ukrainian state. The attempt to do so will only prolong a disastrous war as it would require a military reconquest of the east of Ukraine and Crimea — which it is impossible for Ukraine to achieve and which would be reactionary given the policies of the Ukrainian government against the large Russian speaking minority in the east of Ukraine. De facto Ukraine has already split.

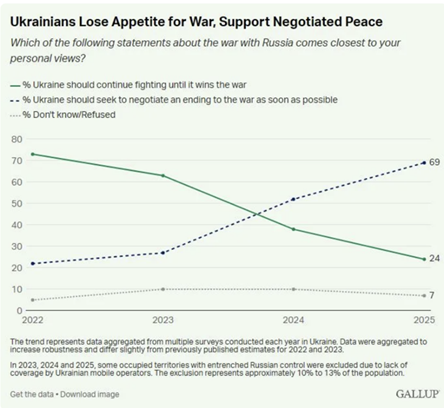

Europe’s leaders, by maintaining the fantasy that the unity of the Ukrainian state can be maintained under these conditions, are prolonging a doomed war, which Ukraine will not win, but which, if it continues, will cost tens, more probably hundreds of thousands, more lives. They are also completely out of touch with the reality of overwhelming majority opinion in Ukraine. The latest Gallup poll of Ukrainian opinion, carried out in August, found 69% of the Ukrainian population believed “Ukraine should seek to negotiate an ending to the war as soon as possible” compared to only 24% who believed “Ukraine should continue fighting until it wins the war” — that is a majority of almost three to one.

But instead of dealing with these realities the statement by European leaders prior to the Alaska summit, and since, avoided both serious issues. For example on 9 August they announced they were: “upholding our substantive military and financial support to Ukraine, including through the work of the Coalition of the Willing” and calling for the “territorial integrity” of Ukraine. Zelensky responded that they: “would not give up their land.”

In reality, it was Zelensky and extreme right-wing forces in Ukraine who recklessly gambled and lost, thereby destroying the unity of the Ukrainian state. Prior to 2014 no serious political force in Ukraine favoured the splitting of the state — as Ukraine was both a bilingual state, with institutional guarantees for the Russian speaking minority and neutral between NATO and Russia. Once these were overturned inevitably the disintegration of Ukraine began.

Zelensky and the extreme, in some significant cases explicitly pro-Nazi, right gambled that that they could introduce institutional discrimination against the Russian speaking minority, and gambled that with U.S. backing they could bring Ukraine into NATO — despite Russia making clear that this would be to cross a red line. In doing so Zelensky and the extreme right destroyed the bilingual/binational Ukrainian state and have led to the devastation of their own part of that state. That is the price they are paying for their reactionary gamble.

But the rest of Europe’s people in particular, and more generally the world, is also paying a terrible price for this failed gamble. Europe’s economy has replaced its cheap energy supply of Russian gas with expensive U.S. liquid natural gas — a key U.S. aim. As a result of these and related policies, Europe’s economy has been pushed into extremely slow growth. Now NATO is attempting to push through huge European increases in military spending which will inevitably be paid for by reductions in social protection and spending. This aim, of using the military spending on the Ukraine war to undermine social protection in Europe, is more and more proclaimed by Europe’s leaders — for example most recently in Merz’s statement that Germany can no longer afford its welfare state, although it apparently can afford a massive military build up that will take place at the expense of that social protection. The inflation generated by the war damaged many Global South countries.

To restore progress in Europe it is necessary to pursue a totally opposite course to the one that led to the Ukraine disaster.

The devastating mistake of expanding NATO must be reversed, including that Ukraine will not be part of NATO. Instead a policy of détente and peaceful relations, and peace ensuring measures, with Russia needs to be pursued.

The increase in military spending must be reversed and priority given to the social well being of Europe’s people.

To revive Europe’s economy it must re-establish economic links with Russia, to regain access to its previous supply of lower priced energy.

The division of Ukraine that will now take place was unnecessary. Ukraine’s unity could have been maintained if the pre-2014 policy of respecting the rights of the Russian speaking minority and a policy of neutrality was maintained – but it was not. The shattered vessel cannot be put back together again. A refusal to face this fact will simply prolong the agony, leading to the loss of tens or hundreds of thousands of lives in a futile quest to achieve the impossible. Europe’s and the U.S.’s leaders are incapable of piloting Europe and its people out of the impasse unless they face the realities of the situation and reverse course.